A blockbuster for the Left

Art Turning Left: How Values Changed Making 1789–2013 is a thematic exhibition curated by Eleanor Clayton and Francesco Manacorda of Tate Liverpool in collaboration with Lynn Wray, whose doctoral research provides the rationale for the curatorial project and the bulk of the research on which it depends. At every opportunity the curators have pointed out that this is ‘the first exhibition’ to examine the intersection of art and left-wing politics that does not merely collect together political artworks or survey the legacy of the avant-garde as a predominantly left-wing force, but rather focuses on, as Manacorda says, ‘key left-wing values such as collectivism, equality and the search for alternative economies’ from the French Revolution to the present day. The selection of these values and the interpretation of them, as well as the decision to frame the Left’s relationship to art in terms of values, is a hazardous exercise. Either the values are shared by Proudhon and Marx, Althusser and E.P Thompson, Keir Hardie and Tony Blair, or the values do not represent the Left in the fullest sense. This is an unusual question to ask of an art exhibition, which is a tribute to the curators, but it is a question that the exhibition cannot quite resolve.

Curators are always judged on the decisions they make, including the selection of the works and the articulation of the theme; however, this exhibition divides the works up according to themes that the curators claim belong to the history of left-wing politics. But this claim is questionable and conceals the questionable decisions made by the curators. If these themes are not successfully grafted onto the tradition, or there is a shortfall between these themes and the artworks selected to demonstrate them, then it is the curators, not the artists, who are at fault.

‘There are three core values that are common to all left-wing ideologies’, Wray says in her essay accompanying the show. Rather than formulate precisely what these values are, however, she offers three graduated normative oppositions: equality rather than hierarchy, progress rather than the status quo, and collectivism and solidarity rather than competitive individualism. Apart from the absence of critique, resistance, opposition, protest and revolution, unfortunately these normative gradients appear to be emblematic of the revolutionary bourgeoisie rather than the long history of the Left. To be clear, the equality of individuals in the marketplace was set against feudal hierarchy by the reformist bourgeoisie; industrial progress confronted the landowning status quo during the transition from feudalism to capitalism; and the bourgeoisie always held off the anarchy of competitive individualism with concepts such as the ‘invisible hand’ of the free market, along with ideological notions of the family and nation.

By contrast, the opposite of equality for the Left is not hierarchy but inequality in all its forms, including the class divisions of formally equal participants in the marketplace; and while the Left has been future-oriented, it has not normally believed in a neutral concept of progress, insisting instead on the transformation of the forces of production (technology, etc.) according to the transformation of the relations of production (class, gender, race, etc.); finally, while fraternity has proved to be the most troublesome of the original three virtues of the bourgeois revolution, and collectivism or the commons remains one of the touchstones of left-wing thinking, its opposite was always better understood as private property rather than competitive individualism. What’s more, by organizing this exhibition according to graduated normative oppositions, the curators deviate from the dialectical tradition in which apparent oppositions are understood as torn halves of a contradictory totality. This raises the question of whether Art Turning Left follows a left-wing approach to historical material in its techniques of inquiry and presentation.

In addition to the problem of whether the curators have successfully distilled from the Left its core values, there is the problem that this rationale abstracts away all divisions within the Left. Subsuming left-wing politics under three abstract values extracts ideas from their social history, which contradicts the methods distinctive to left-wing analysis, especially within art history and cultural theory. What’s more, formulating these values in their ideal form, rather than in their historical specificity, insulates them from critique, proposing a consensus of values where there has always been detailed internal rivalry of principles, strategies, tactics, methods, means and aims. There is no orthodoxy for the curators to adhere to in order to cement the left-wing character of the exhibition. On the contrary, even Marxism, which has no monopoly on the Left, was divided during the Cold War into Western Marxism, Classical Marxism and Soviet Marxism, and has since been divided into Leninism, Trotskyism and Maoism, not to mention various forms of post-Marxism. Rather than attempting to identify the shared values of the Left, or, better still perhaps, the central questions that the Left has contested among itself, it would have been more worthwhile, and more in keeping with the history of the Left, to identify left-wing methods of treating historical material. The point that must be stressed is that the intellectual Left has always contested its internal political disputes through its methods and techniques rather than absolve itself through the presentation of facts, values and narratives.

A large survey exhibition of left-wing art is simultaneously symptomatic and atypical of art museum exhibitions in the era of the blockbuster, in which art’s institutions have been subsumed under the economic hegemony of global spectacle – a tendency Tate Liverpool has promoted. But this familiar format is filled here with works that lack the glamour and popular appeal that it characteristically requires. The blockbuster exhibition format, which began with several large-scale retrospectives of modern ‘masters’ in the 1960s, was inaugurated with the Tate’s Picasso retrospective of 1960, for which Tatler coined the term ‘block-buster’. An immediate popular and financial success, with record attendances, record sales of postcards and catalogues, and what appeared to be a national art event, the official history of the blockbuster argues that previously the general public had rejected modernism, while the blockbuster format created the buzz that made it popular.

Alan Wallach argues that the heroic period of the museum operating at the forefront of artistic developments, with exhibitions of Cubism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and Op Art, gave way to a nostalgia for utopian modernism, exemplified in the blockbuster. This account is ideologically opposed to the official story, but both fit the facts. The blockbuster is a popular nostalgic format for converting the history of art’s future-oriented critique into spectacle and revenue. Indeed, this was its express purpose. It was the presence of corporate trustees in place of academics that brought about the blockbuster as one of a series of innovations to ‘raise money, augment membership, run sales operations, direct production of museum publications and oversee food services’, such that, by the 1980s, in the words of Jonathan Harris, ‘the days of genteel amateurism were all but over’. Wallach’s point is more serious than this, though, arguing both that the future had been relocated in the past, and that critique had migrated from curatorial method to spectacular content.

In one sense, then, the blockbuster exhibition temporarily expropriates works that have entered private collections for the public, a format that increases revenue and extends art’s audience but, at the same time, tends to be conservative. Each blockbuster ‘is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity’, says Iwona Blazwick, the director of the Whitechapel Gallery, but, taken as a whole, as a format, the blockbuster has become so routine that it is almost impossible to experience art in museums in any other way. Having said this, it should be noted, as Wallach does, that there is an alternative to the blockbuster, usually occupying the second tier of museums, in which artworks and other objects are assembled for the purpose of calling up their social history and even ‘subject[ing] the category “art” to a searching examination’. The key to the museum’s rejection of the blockbuster, therefore, is the production of a critical relationship to the exhibited material.

Blockbusters have usually capitalized on celebrity and conservative values, including nationalism and imperialism, hence the theme of left-wing politics in art is untypical. Since critique only makes its way into Art Turning Left through its content rather than its curatorial method, the theme of left-wing values need not subvert the blockbuster form. Art Turning Left is a blockbuster in its scale, in its thematic organization, in its bringing together in one place a range of historically significant artworks, and with its merchandise, the inevitable catalogue and so forth. But is it a blockbuster of the Left? Or is it, by dint of its content or some technical aspects of its organization and display, a critical cousin of the blockbuster?

Although there is a timeline in the catalogue, the exhibition itself gathers works together around the values that the works putatively share. Some Situationist International montages are placed within eyesight of a copy of Jacques-Louis David’s painting Death of Marat from 1793, which is in close proximity to a wallpaper design by William Morris from 1881. It would be productive to allow these works and their historical contexts to resonate off one another – David’s classicism and Morris’s medievalism, for instance, dressing up the revolution in old clothes, while the SI refunctioned contemporary consumerist culture. But the criterion for their overlapping ‘value’ is predetermined by the exhibition, which brings the works together around the question ‘How can art speak with a collective voice?’ After cutting up the history of left politics into ideal parcels, the curators have to squeeze actual works into them. The result is both less and more than was intended. The problem is not that the dialogues established between works misfire or are fictitious, but that the variety of ways in which these works might occupy the complicated and contested tradition of the Left is not articulated. The exhibition is more interesting if we ignore the curatorial rationale and all its cues.

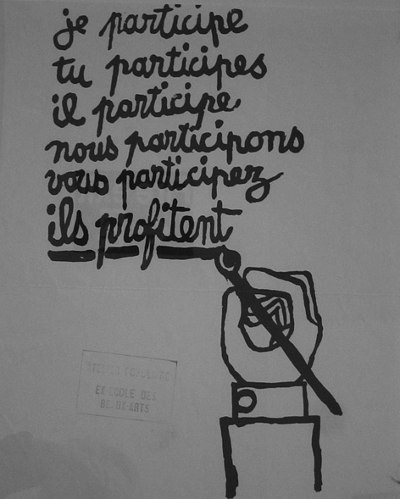

Art Turning Left translates its three values into seven questions, which appear on the walls of the museum as headings under which artworks sit. ‘Do we need to know who makes art?’ brings together works that have been produced collaboratively and anonymously, thereby recasting the value of collectivity in terms of anxieties about authorship. ‘Can art affect everyone?’ struggles to contain a group of artworks that thematize solidarity, revolution, war, alienation, domestic labour, crisis, craftwork, industrial design and formal experimentation. ‘Can art infiltrate everyday life?’ brings together works that thematize the everyday alongside others that take the form of popular culture or utility, and yet others that address the masses, including a photo-novel by Allan Sekula, embroidery by Liubov Popova, a Suprematist dress design, various works related to propaganda including a gouache design for a speaker system, and two works by Chto Delat. ‘Does participation deliver equality?’ incorporates some works that are participatory and some that are archival rather than participatory. Equally lacking in precision and pertinence, the exhibition also asks ‘Can pursuing equality change how art is made?’ and ‘Are there ways to distribute art differently?’

Couldn’t Popova’s constructivist designs legitimately occupy a place under every question in the exhibition? Indeed, the whole arrangement of works could be changed on a daily basis, moving works from one value to another on a perpetual merry-goround, without losing any of the sense purportedly created by the headline questions. Not only is the place of each artwork within the exhibition arbitrary, as is the case for curated theme shows in general, but the specific sub-theme allotted to groups of works appears arbitrary too. This takes nothing from the individual works seen in isolation. Chto Delat’s video Partisan Songspiel: A Belgrade Story, 2009, is displayed in its own room with a comfortable bench so that a few people can watch the whole epic performance incorporating choir music, dance, theatre, modernist sets and prop-sculpture. Walter Crane’s monumental trade-union banner of 1898 is provided with an echo by the close proximity of Braco Dimitrijevic’s wall-sized photo of a passer-by exhibited in a public site during the 1976 Venice Biennale. Many of the works benefit from their juxtaposition with others in the exhibition, which is genuinely pleasurable and enlightening. Unfortunately, however, it is not the various sub-themes of the exhibition that establish the strongest and most rewarding relationships between the works.

More than just a curatorial novelty, the focus on left-wing values is a political act in its own right. But expressed in all its abstraction it is impossible to discern the specific political character of the shift away from the politics of art to the political values that art has, or appears to have, adopted. Art Turning Left is explicitly not an exhibition of political art in the narrow sense, but there are other exhibitions that it might have been. The exhibition is haunted by these alternatives because it fails to make its own case. Curated exhibitions are always disturbed by the long shadows cast by works or artists that are absent from them. A piece in this exhibition by the Guerrilla Girls from the mid-1980s makes the point that the under-representation of work by women and black artists from major art institutions has to be accounted for and put right. An exhibition that bills itself as surveying the relationship between left-wing politics and art was inevitably going to be judged in terms of its exclusions, biases and blind spots, given the divisive history of the left. Politically, it is important to take notice of all the left-wing art exhibitions that this show is not.

This is not an exhibition that revisits the actual questions raised by the political Left about art. Conspicuous among these questions have been the following. Should the transformation of art wait until after the revolution? Rather than funding art, shouldn’t we use public funds to save lives, help the poor, subsidize free education for all, or abolish Third World debt? Is art ideology? Is it the culture of the dominant? Is art functional for the existing society? Is art autonomous? Is art elitist and ought art be populist, realist, utopian, avant-garde, free? Is art an example of free labour, unalienated labour, intellectual labour? Does art correspond to the consumerist practices of free time, leisure, decor, luxury? Is art condemned to be high culture in contrast with the low culture of the dispossessed? What is art’s role in the maintenance of cultural distinction and the accumulation of cultural capital? Should art change the world or should art be abolished along with all forms of privilege, exploitation and wealth?

This is not an exhibition structured around the major aesthetic debates of the intellectual Left. There is no trace of the theories of art’s reification, commodification, complicity, real subsumption or art’s participation in the culture industry, nor of the many disputes between artists and left-wing orthodoxy, particularly the tension between Surrealism and Stalinism or, again, between Formalism and Realism. Trotsky’s advocacy of a revolutionary art appears as irrelevant as the far-left call for the abolition of art. Tensions of this type are stronger candidates for any survey of art’s relationship to left-wing politics, indexing actual works not to ideal abstract values but to real oppositions that are no less normative for that. What the history of left-wing aesthetic debates has demonstrated time and time again is that the politics of art cannot be reduced to the thematization or application of politics proper, but must be understood as a specific politics mediated by the history and social relations of art and its materials. Rather than assuming that art has been influenced by left-wing politics in general, one of the distinctive contributions of the Left has been the argument that art is a practice of values that are inflected politically in the qualities of works themselves. Exploring the 68 mediated relationship between art and politics is yet another exhibition that Art Turning Left is not.

By inquiring into how left-wing values have penetrated art, the exhibition inevitably restricts itself almost exclusively to work by artists, neglecting both the left-wing rejection of artistic production and the full range of vernacular left cultural forms produced by amateurs, communities and philistines. From the ‘liberty cap’ to the ‘book bloc’, and including all the posters, banners, slogans, chants and badges of political activism, these forms enter the exhibition only in so far as they pass through artistic projects such as Jeremy Deller and Alan Kane’s Folk Archive, or Ruth Ewan’s A Jukebox of People Trying to Change the World. While the hypothesis of the exhibition appears to foreground the left-wing political tradition in relation to art, the presupposition that left-wing values become expressed in art leads to a conservative emphasis on the artist, even if, on occasion, the artist collaborates with others or urges them to act. The inclusion of artworks that critique the ideology of the artist, such as Live and Let Die Collective’s comic strip of the death of Duchamp, in no way counter balances the structural dependence of the exhibition on the artist.

Oddly, one of the most telling exclusions is a generous portion of bad art. Arthur Dooley, a prominent and popular Liverpool sculptor in the 1960s and 1970s, was an outspoken left-wing artist who believed that art should speak in the language of the working class, based in their relationship to labour, skill, community and the city. Dooley may have represented a relationship between art and the Left that has gone out of fashion – and was always deeply conservative vis-à-vis the history of art – but that is no reason to exclude him and all those artists who shared his convictions. Contrary to the actual demands made on art by the political and intellectual Left, the exhibition is determinedly sophisticated, elegant, inventive, clever, informed and tasteful. If this exhibition is meant to be taken as a representative of the full range of left-wing values in art, it creates the myth that the Left has produced nothing but a string of the most exciting and substantial art of the last two and a half centuries. Filling an exhibition with the likes of Bertold Brecht, Jean-Luc Godard, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, Mary Kelly, Martha Rosler, Aleksandr Rodchenko, El Lissitzky and Sergei Eisenstein makes for a smashing day out, but it is a version of the Left closer to Tony Blair’s ‘spin’ than to E.P. Thompson’s history.

⤓ Click here to download the PDF of this item